Quiet Creatures: A Summer on Long Island

Masters thesis, 1998, Religous Studies, Univ of Colorado (download pdf)

Abstract

I spent a summer working in a marine biology lab on the north shore of Long Island, padding along the local beach, watching the dramas of animal life there and searching for the keys that would make sense of them: the avenues along which I could enter the animal’s home and feel myself at home. These desires—for a sense of logic and order in nature, and a sense of home and family—I see reflected in many other naturalists, from Gilbert White in the eighteenth century to Edwin Way Teale and Annie Dillard in our own.

The landscape I observed answered and rejected those desires simultaneously. The biological world is neither exactly logical nor a chaos; neither a ball of warm sentiments nor cold and aloof. It runs on other principles: a musky, tactless intimacy, and a meandering logic, full of reversals. We are absorbed within a complex organic system and fully dependent upon it, linked to millions of species, each with its own way of getting along, by a great web of family relationships.

Intimacy in a landscape consists, for the most part, of digestion: gory and grotesque, but also smooth, balanced, and eternal, what Paul Shepard calls “a universal metabolism.” Our human pursuits blend into this metabolism smoothly: the death of a creature under a microscope isn’t so different from the death of a creature between a pair of jaws. When we ignore such congruencies, however, as our body-distaining culture encourages us to, our inquisitiveness turns sour, and yields odd, unwholesome relationships. The alternative—so simple in the abstract—is to accept our full participation in animal life. We live within a great mystery: the mystery of bodies and their conjunctions, and, too, the mystery of how we, inquisitive and posturing, awestruck and cocky, rise from its midst.

I’ve written this as a personal essay, because these are personal issues, inextricable from my own desires and my own wrestling bouts with specific animals. I have tried to give a voice to the creatures I encountered on Long Island; I found that they had much to say, and sly and grave ways of saying it.

An excerpt about horseshoe crabs

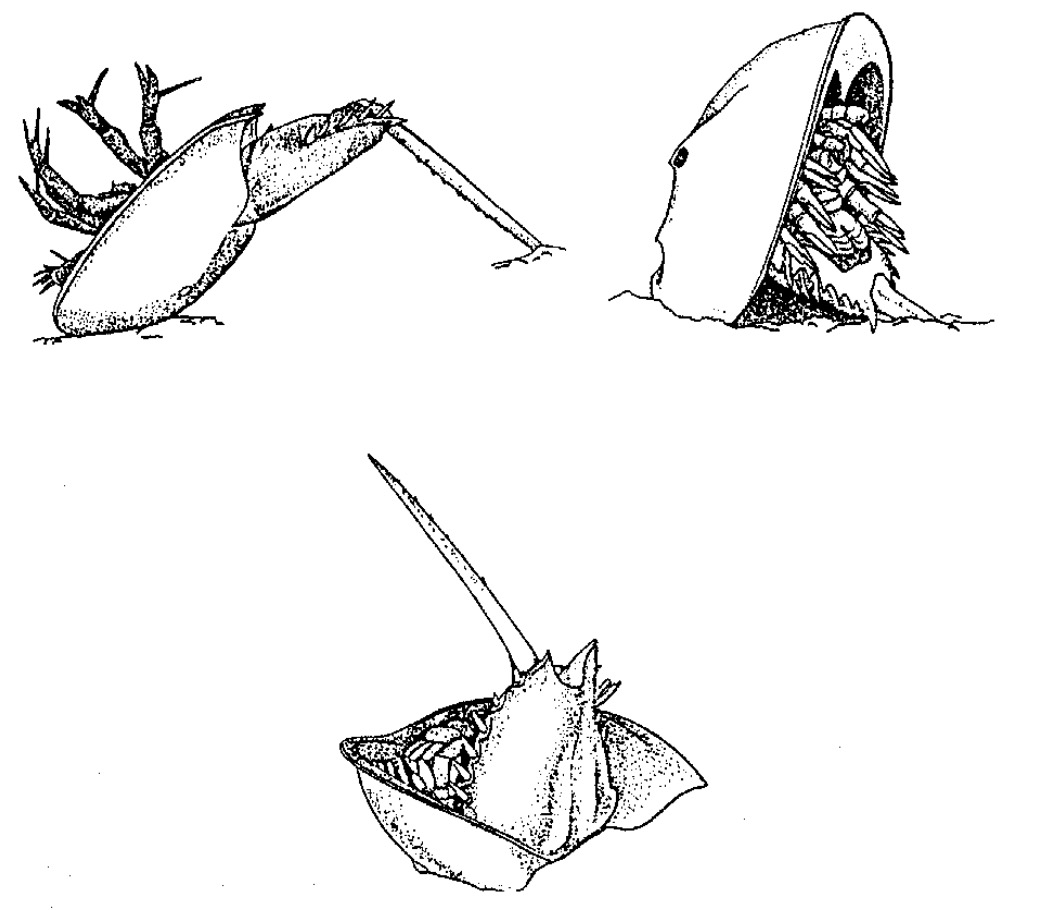

Horseshoe crabs are eccentric animals. They are, more precisely, inverted frying pans that occasionally wag their tails. A visitor most often sees them heaving themselves over the sand, or dead, and in these states they seem more contraption than creature: in fact, the two states are barely distinguishable. In the water, however, where they hide like shadows, fuller personalities unfold. “Horseshoe crabs scuttle,” wrote one marine scientist, “and scuttling is the same as scampering.” They’re actually lively, it occurred to me with a start, the first time I saw them swimming by my ankles. They turn and they bobble; they jet forward and suddenly hunker down.

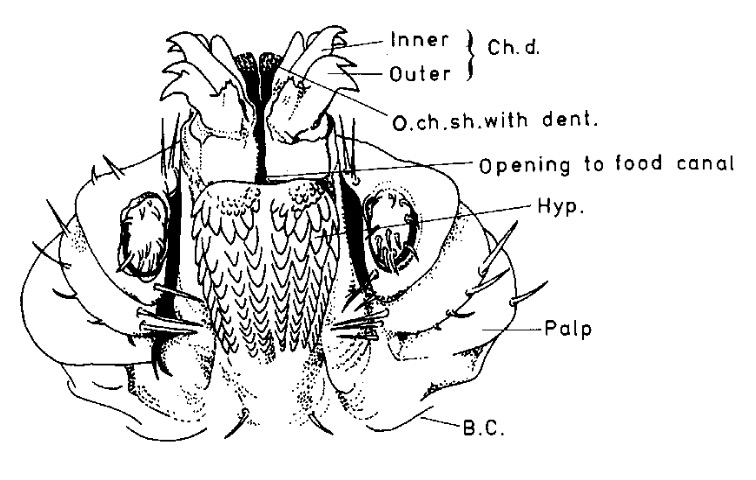

They test everything they pass over with pincers hidden underneath their round shells. They’re searching for clams, worms, dead fish, anything edible. They seem much more suited to pincering than to analysis; during the mating season, for example, males will try to mate with anything in their path, rocks and toes alike, until it’s been thoroughly established by feel that the something is not a female horseshoe crab.

They’re lunks, but at the same time they carry with them—like every wild animal I can think of—a specific, proprietary dignity. They live with perfect composure, as if after this length of time they’ve casually come to trust the landscape to shape itself to them. The longer I spend with them, the more I feel compelled to uphold that trust, never to betray it with violence or crassness. Their behavior, so completely contained, asks for the maintenance of a respectful distance—while also suggesting a kinship, an equivalence, between my activities and theirs.

Another bit about ticks

If there’s any place on Long Island where one can go to contemplate nature in its purity, it isn’t Indian Island, a one-hundred-RV campground just barely outside the city of Riverhead. I was in such a good mood, though, that I did anyway. I serenely contemplated nature from the park’s tiny beach. I serenely contemplated in the leafy woods, I contemplated more inquisitively, but still serene, in the strip of odd scrubby dunes between them. The land was woven together perfectly, fresh and clean. The sun was hot; I scuffled back to the campground, towel slung over my shoulder, the dirt road wandering up between my toes. A boy from a nearby campsite beamed as he introduced me to his dog, which I scratched behind the ears. Here was the archetypal Independence Day weekend: I saw nothing on the American continent today but friends and neighbors. I was raised up from the rich soil like Adam; I was a dweller in Eden, at home in a landscape of generous hospitality. And in the car on the way home, I found a fat tick dug into the back of my shoulder.

I imagine it sidled onto me as I brushed against some stem and then crawled up the outside of my shirt, under my collar, and down my shoulder blade until it found a spot it liked. It must have found me while I was in the woods that morning, which means that there was a three-hour stretch in which the tick was sipping at my blood, as serene as I was. But when I found it welded to me in the car, I ruined the blissful moment for both of us in a hurry—my own hospitality, apparently, not so generous.

I ripped it off—not the wisest thing to do with ticks, especially in the land of Lyme disease—luckily a piece of my skin came off with its jaws, rather than its head coming off its neck and staying buried in me. I felt a little crazed. Vanessa kept on driving; I trapped the thing in a fold in a plastic bag and did my best to murder it. It was a quarter of an inch long, a sickly beige, and, incidentally, one of the horseshoe crab’s closest living relatives, though this was not on my mind at the time. I was too busy hating it, scorning it, staring in awe at it, and fearing it in quick succession. I wasn’t observing very closely what the tick was doing during this time: wriggling, probably, losing some legs under my fingernail, definitely not dying. I finally flung the tick out the car window and it whipped behind us at fifty miles an hour. I wouldn’t be surprised if it made it back to the woods.

There’s no war-glory in these encounters, none of that crimson-streaked, lion-taking-down-a-springbok atmosphere that the nineteenth-century Romantics and their modern successors—TV wildlife specials— find so satisfying. There’s precious little of it out in the wild anywhere. Animals in general just aren’t angry at each other, even when they’re eating each other, and they fight dirty. Most of the violence in the world isn’t combat, but something slower, more banal, more sniveling.

Nature isn’t really so red in tooth and claw; it’s more like black comedy, occasionally dry and understated like the dead kelp on a beach, more often slapstick. The world’s full of raucous marauders (like the gulls who snatch up spider crabs and drop them on the rocks from forty feet up, repeatedly, to crack them open), practical jokes (like the spider crabs discovering that out of the water they’re too weak to lift their own pincers to defend themselves), and plenty of raw meat—a real carnival, in the sense of the word that honors its linguistic link with carnal, carnage, and chili con carne. Try to spend a weekend inhabiting a nobler or friendlier kind of wilderness, and some greasy critter shows up on your shoulder to remind you how good you taste. This is our family. We’re going to be meeting at these holiday barbecues till the end of time.