Compared with most large, temperate estuaries, the biogeochemistry of Puget Sound is highly marine dominated: 70% of dissolved nutrients come from the Pacific. Nevertheless, there’s significant policy and management interest in understanding watershed contributions of environmental stressors, e.g. nutrient loading in relation to hypoxia, and pathogen and pollutant impacts on commercial, recreational, and tribal shellfish harvesting. But given that Puget Sound is fed by 16 major rivers that vary by orders of magnitude in flow volume, which watershed is responsible for freshwater, nutrients, and pathogens found in a given area of Puget Sound at a given time? Should water quality problems be thought of as local or nonlocal?

This paper…

Banas NS, Conway-Cranos L, Sutherland DA, MacCready P, Kiffney P, Plummer M (2014) Patterns of river influence and connectivity among subbasins of Puget Sound, with application to bacterial and nutrient loading. Estuaries and Coasts, doi:10.1007_s12237-014-9853-y. (download pdf)

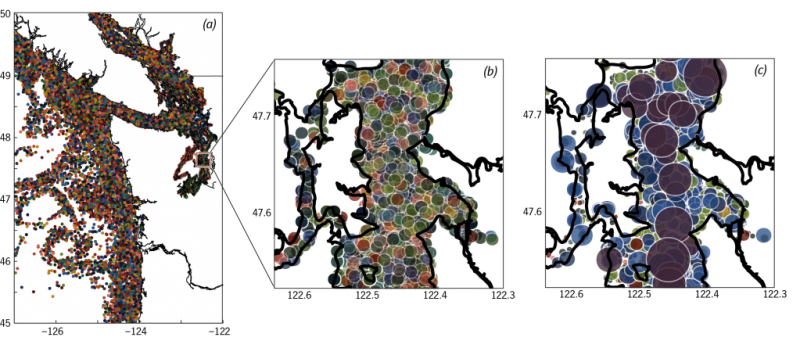

…uses a comprehensive, particle-based reanalysis of an existing hydrodynamic model (Sutherland et al. 2011) to systematically address the questions above. We tracked 130,000 particles over a full year, attempting to account for and track histories of all of the freshwater entering Puget Sound. Which raises a methodological question: Are our current Lagrangian methods actually capable of reconstructing entire tracer fields in complex domains (here, total freshwater content, i.e., salinity)? We almost never attempt this; we tend to track just a corner of a tracer field and implicitly assume that if we scaled the method up we would not uncover major conservation errors. Here we actually check that assumption.

Conclusions

- The reconstruction of volume-mean salinity over time from >100,000 particles is quite good in some basins but significantly biased in others. Intriguingly, the errors in the Lagrangian reconstruction of the underlying Eulerian model are largest where the errors in the Eulerian model are also largest: deep in the landward reaches of South Hood Canal and South Sound. We suspect that any modern, practical particle-tracking scheme would show a similar slow degradation in accuracy, if used to track particles for hundreds of days in strong tidal flow in narrow, steep topography.

- River contributions to total freshwater content in Puget Sound are highly nonlocal, but that the influence of bacterial and nutrient loading by the same rivers is much more local. The common, implicit assumption that river influences on water quality at a given site reflect the impact of the nearest major river is a good rule of thumb for pathogen and nutrient loading for most of Puget Sound, throughout the seasonal cycle—but for freshwater itself and long-lived river-borne tracers, this rule of thumb could be quite misleading in spring and summer. In other words, local salinity cannot be used as a reliable indicator of the influence of local rivers on water quality, even to a first approximation, except perhaps within a few km of a river mouth.